This blog reports on research I conducted into two widely used terms in communicative language teaching; ‘information gap’ and ‘jigsaw’, as part of a wider research project for my book Activities for Cooperative Learning in the Delta Publishing Ideas in Action Series, and my work on a taxonomy for jigsaw activities, presented in this article for Modern English Teacher. An interesting finding of this research is that both the jigsaw and information gap activities that today language teachers use mainly to facilitate interaction in communicative classrooms trace their origins to materials designed to support the integration of minority students in mainstream education, albeit in two rather different contexts.

The origins of jigsaw in… desegregation

The use of the term ‘jigsaw’ to refer to a pedagogical activity originates in the work of Eliot Aronson and his graduate students in 1971 (Aronson et al., 1978). Then a developmental psychologist at Austin University, Aronson invented this, the fundamental information gap activity, as a solution to interracial conflict during the period of desegregation in American schools in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Aronson and his research team experimented with activities in which different groups of students received different textual content that they read and then shared with students from other groups in information-exchange activities (Aronson et al., 1975), similar to what language teachers today might call a ‘reading jigsaw’. Designed for all subject lessons, jigsaw was seen as an alternative to the competitive activities then dominant in US schools, one that could get students from different ethnic backgrounds cooperating and learning together in the classroom. Aronson called his approach “The Jigsaw Classroom” (Aronson et al., 1978), and later recalls:

“We realized that we needed to shift the emphasis from a relentlessly competitive atmosphere to a more cooperative one. It was in this context that we invented the jigsaw strategy. Our first intervention was with fifth graders. First we helped several teachers devise a cooperative jigsaw structure for the students to learn about the life of Eleanor Roosevelt. We divided the students into small groups, diversified in terms of race, ethnicity and gender, making each student responsible for a specific part of Roosevelt’s biography.” (Aronson, 2000)

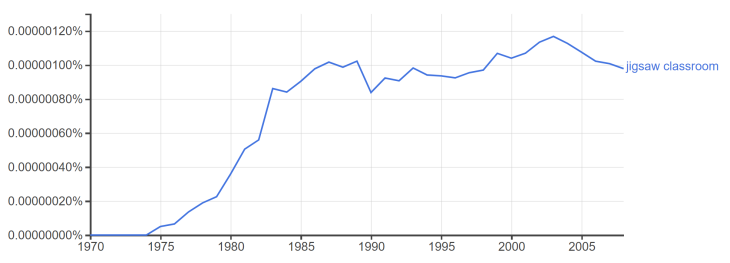

Aronson’s work was part of a wider cooperative learning movement, popular at the time, that also included other psychologists (e.g., David and Roger Johnson; see Johnson et al., 1973), all of whom emphasised elements of cooperation and collaboration—rather than competition—in the activities and principles they introduced into classrooms (Anderson, 2019b). A central emphasis of this movement, and of jigsaw activities, was peer teaching, and the “positive interdependence” that it fuelled, increasing harmony in the classroom (Anderson, 2019c). Unlike in language teaching, where such jigsaw texts tend to be seen principally as fodder for reading and speaking skills practice, in mainstream classrooms, the content, and its successful peer transmission is an essential part of effective jigsaw, even today (e.g. Berger & Hanze, 2015). Jigsaw quickly caught on (see Figure 1).

The term ‘jigsaw’ entered the rapidly expanding communicative language teaching (CLT) movement at the end of the 1970s, with Geddes & Sturtridge’s Listening Links (1979), the first book of jigsaw activities for English language teachers (Johnson, 1981, although see Watcyn-Jones’s 1978 publication discussed below). Geddes & Sturtridge had transformed it into a listening activity, then compatible with the large number of language laboratories found in language schools at that time. In Listening Links, after listening to 3 different ‘texts’, learners got together in groups to share the content. Their topics included party gossip, flat hunting and ‘a day out in London’, all themes that would become familiar among coursebooks over the next decade. Geddes & Sturtridge also produced a book of reading jigsaws, called Reading Links (1982). References to jigsaw soon appeared in more theoretical publications on CLT (e.g., Johnson, 1981; Littlewood, 1981), and variants soon appeared (e.g., Ur’s “Combining Versions”, 1981, p. 90). While jigsaw activities were common through the 1980s in resource books (e.g., Hadfield, 1984), and occasional in coursebooks (e.g., Swan & Walter, 1985), it wasn’t until the 1990s that jigsaw readings, similar to those used by Aronson, became common in mainstream ELT coursebooks (e.g., Soars & Soars, 1991). Klippel’s Keep Talking (1984) is the only book within CLT at that time that I have found that credits Aronson and colleagues as the originators of jigsaw. Jigsaw reading activities have remained popular in global ELT coursebooks ever since (e.g., Redston & Cunningham, 2013).

From the 1980s onwards, a number of SLA researchers began using the term jigsaw, especially in research on task-based language teaching, albeit with varying definitions. While some see it as essentially synonymous with information gap (Walz, 1996), others make a distinction between “two-way” tasks (with both participants needing to convey information) such as jigsaw, and “one-way” tasks (with only one conveying the information) as in Describe and Draw (e.g., Long, 2015; Pica et al., 1993; Swain & Lapkin, 2001). Notably, Pica et al. (1993) separate jigsaw from information gap (the latter classified as only one-way), arguing that jigsaw is superior for the greater interaction opportunities it provides. All these authors overlook jigsaw’s origins in Aronson’s work.

My recent definition retains Aronson’s original two-stage description of jigsaw as follows, but seeing it as a type of information gap (within language teaching):

“A jigsaw is a cooperative information gap activity with two stages. The input stage involves input of information (usually a text), with different learners accessing different information to create the information gap. The communication stage follows this, and involves communication of that input to others in pair or group interaction.” (Anderson, 2019a, p. 35)

So where did ‘Information gap’ come from?

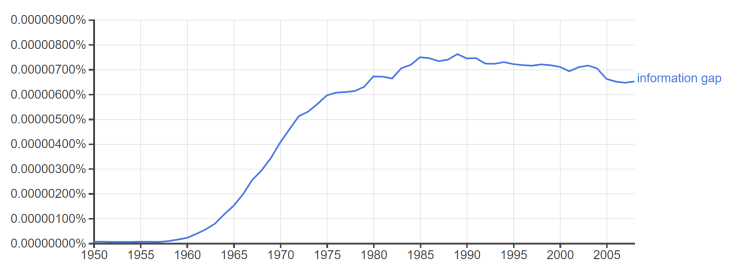

The term ‘information gap’ seems to become common in general discourse during the 1960s (see Figure 2). Most of these early references, from a range of fields, seem to use the collocation literally. Like ‘jigsaw’, it seems to appear quite suddenly in language teaching in the late 1970s, to refer to a communicative activity, with several references in published works in 1979 (e.g. Byrne & Rixon, 1979; Johnson, 1979; Morrow & Johnson, 1979; Rixon, 1979), all from the UK. However, I found one earlier mention by Long (1976), possibly the first published reference to information gap as a language teaching activity. Long’s paper argues for more communicative pair and groupwork activities in the classroom than were then typical:

“Implicit in the discussion so far, and now made explicit, is the suggestion that relevant experiences for adults undergoing formal instruction in English need to include their being placed in problem-solving situations where the bridging of an ‘information gap’ will require communicative use of the target language on their parts.” (Long, 1976, p.9, quotes in original)

Long recommends the use of communication games, citing a paper presented by Allwright the previous year, 1975*, as a source for these. Allwright’s written paper of a similar title (1976) includes description of a typical match-mine information gap activity. Long’s earlier paper on a similar topic (1975, p. 221) describes a groupwork role play including preparatory role cards as creating an ‘inferential gap’. Three years later, Watcyn-Jones (1978) publishes probably the first compilation of communicative role plays for pair and groupwork, each role with a corresponding card. Interestingly, Watcyn-Jones also includes several ‘Making the Right Choice’ activities; simulations rather than role plays, in which pairs accesses different texts (e.g. 2 different house advertisements from an estate agent) before agreeing on the best one for a couple. These are early examples of non-role-play textual jigsaws.

An earlier origin for information gap activities

Shortly after this, Byrne & Rixon’s (1979) volume of communication games (available here), and Rixon’s (1979) brief article entitled “The ‘Information Gap’ and the ‘Opinion Gap’—Ensuring that Communication Games are Communicative” locate information gap activities firmly within the then new communicative approach, as cooperative games. Byrne & Rixon define communication gap as

“… a built-in disparity of information or opinion amongst the players. If a situation is created in which one player knows something that another does not and the information needs to be shared in order that they should complete some task, there is an automatic need to communicate, and communication will usually take place.” (Byrne & Rixon, 1979, p.9)

Both sources provide a now familiar example, Describe and Draw, something that Rixon (pers. comm.) had found in a much earlier set of teaching materials also mentioned by Howatt (2004, p. 334), and thus may have been known to both Allwright and Long: Concept 7-9 (University of Birmingham, 1972). Concept 7-9 was originally designed for developing communication skills among EAL (English as an Additional Language; then referred to as ‘immigrant’) students to support their integration into mainstream primary school classrooms in the UK. They included a range of other information gap activities (although not labelled as such) that were also adapted by Byrne & Rixon, whose volume of communication games may be the first published compilation of (non-role-play) information gap activities for mainstream ELT, although both Wright (1976) and Byrne (1978) do include some activities (e.g., image sets) that could be used for information gap.

Rixon (1979) also introduces an alternative term ‘opinion gap’, for a different, competitive type of game in which learners attempt to disagree with each other. Rixon’s use is the earliest published reference I could find for ‘opinion gap’ in CLT, and Rixon recalls having coined the term herself (pers. comm.). It became more widespread after this to refer to activities that involve almost any comparison of personal opinion — see Prabhu’s (1987, pp.46-7) later discussion of information gap, opinion gap, and ‘reasoning gap’ to refer specifically to problem-solving information gaps. This third term did not catch on as much as the other two.

Information gap as central to CLT

Johnson’s (1979) more academic discussion of information gap does not mention games, but also sees it as central to CLT classroom practices:

“The attempt to create information gaps in the classroom, thereby producing communication viewed as the bridging of the information gap, has characterized much recent communicative methodology.” (1979, p. 201).

Also in 1979, Morrow & Johnson’s early communicative coursebook, “Communicate 1” was probably the first communicative coursebook including regular textual information gap activities, in which students worked in 2 groups (A and B) to prepare for role plays (e.g., asking and answering questions in a tourist information office), similar to Long’s earlier proposal (1975, see above):

“Divide the class into two groups, and tell group A to look only at their instructions in the Student’s Book while group B look only at theirs. It is a good idea to get students to cover the part they are not supposed to look at with a piece of paper.” (Morrow & Johnson, 1979, p. 29)

Although the Strategies series is often seen as one of the earliest communicative courses, during my search I did not find examples of information gap activities in the early editions. ‘White’ Strategies (Abbs et al. 1975), for example, provides numerous scripted pairwork role plays, and ‘Open dialogue’ role plays, in which one member of the pair has to improvise their role, but no information gap activities.

A gap too far?

By 1981, the term ‘information gap’ is already being regularly used and its parameters explored. Maley’s (1981) typology of ‘games and problem-solving activities’ is an early attempt to categorise a range of information gap activities. Morrow, writing in the same year, goes so far as to argue that all communication involves bridging an information gap, even phatic use such as greetings. He notes:

“This concept of information gap seems to be one of the most fundamental in the whole area of communicative teaching” (Morrow, 1981, p.62)**

This centralisation of “transactional language”, and neglect of more “interactional language” (Brown & Yule, 1983; also see Halliday’s ‘interpersonal function’ of language) seems to have been carried forward into early writings on task-based language teaching (e.g., Long, 1985), and is evident in Johnson’s paper (1979), which, as well as being one of the first to define information gap, was also one of the earliest to define ‘task-oriented teaching’ (as it was initially called):

“It is for reasons such as this that fluency in communicative process can only develop within a ‘task-orientated teaching’—one which provides ‘actual meaning’ by focusing on tasks to be mediated through language, and where success or failure is seen to be judged in terms of whether or not these tasks are performed.” (Johnson, 1979, p. 200)

However, the origins of task-based language teaching are somewhat more contested, and may require a separate blog post… 🙂

—————————-

*Long cites as follows: “‘Learning language through communication practice’. Paper presented at the 4th International Congress of Applied Linguistics, Stuttgart, 1975.”.

**More recent research has shown no such privileged status for information gap, and that more interpersonal discussion activities can provide opportunities for richer and more varied language use (e.g., Nakahama et al., 2001), evidence that we should include a wide range of activity types in our syllabus.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the University of Warwick ELT Archive, and Dr. Richard Smith, its curator – without this free archive, such research would not have been possible. Thanks also to Shelagh Rixon, Michael Swan and Catherine Walter for useful pointers and memories!

My research for this piece was not exhaustive. I may well have overlooked non-archived papers and non-published artefacts or events of influence. I welcome any corrections (email j.anderson.8@warwick.ac.uk or comment below) and I will incorporate with acknowledgement.

Changes made since original posting on 24th March 2019:

27/03/19: Changes made to paragraph 5 (SLA), to improve clarity and include further reference (Walz, 1996).

25/04/19: Change made to paragraph 4 (jigsaw in early CLT) to include reference to Geddes & Sturtridge’s Reading Links (1982). Change made to paragraph 9 (Byrne & Rixon’s work) to include Concept 7-9, based on personal testimony by Shelagh Rixon, corroborated by Howatt (2004). Introduction changed to remove reference to my IATEFL 2019 talk (by now in the past).

References

Abbs, B., Ayton, A., & Freebairn, I. (1975). Strategies: Integrated English Language Materials. London: Longman.

Allwright, D. (1976). Language Learning through Communication Practice. ELT Documents (76/3). London: British Council.

Anderson, J. (2019a). Deconstructing Jigsaw Activities. Modern English Teacher, 28(2), 35-37. See here.

Anderson, J. (2019b). Activities for Cooperative Learning: Making Groupwork and Pairwork Effective in the ELT Classroom. Stuttgart: Delta Publishing/Ernst Klett Sprachen. See here.

Anderson, J. (2019c). Cooperative learning, principles and practice. English Teaching Professional, 121, 4-6. See here.

Aronson E., Blaney, N., Sikes, J., Stephan, C., & Snapp, M. (1975). The jigsaw route to learning and liking. Psychology Today 8, 43-50.

Aronson E., Blaney, N., Stephan, C., Sikes, J., & Snapp, M. (1978). The Jigsaw Classroom. Beverley Hills: Sage.

Aronson, E. (2000). History of the jigsaw. Retrieved (2019, March 23) from https://www.jigsaw.org/history/

Berger, R., & Hanze, M. (2015). Impact of Expert Teaching Quality on Novice Academic Performance in the Jigsaw Cooperative Learning Method. International Journal of Science Education, 37(2), 294-320.

Brown, G. & Yule, G. (1983). Discourse analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Byrne, D. (1978). Materials for Language Teaching 1 / 2 / 3. London: MEP.

Byrne, D. & Rixon, S. (1979). ELT Guide-1 Communication Games. London: British Council. Available here.

Geddes, M. & Sturtridge, G. (1979). Listening Links Student’s Book. London: Heinemann.

Geddes, M. & Sturtridge, G. (1982). Reading Links Student’s Book. London: Heinemann.

Hadfield, J. (1984). Harrap’s Communication Games. London: Harrap.

Howatt, A. P. R. (2004). A History of English Language Teaching (2nd ed.). Oxford: OUP.

Johnson, R. T., Johnson, D. W. & Bryant, B. (1973). Cooperation and competition in the classroom. The Elementary School Journal 74(3), 172-181.

Johnson, K. (1979). Communicative approaches and communicative processes. In C. J. Brumfit & K. Johnson (Eds.), The Communicative Approach to Language Teaching. (pp.192-205) Oxford: OUP.

Johnson, K. (1981). Writing. In K. Johnson & K. Morrow (Eds.), Communication in the Classroom (pp. 93-107). Harlow: Longman.

Klippel, F. (1984). Keep Talking: Communicative Fluency Activities for Language Teaching. Cambridge: CUP.

Littlewood, W. (1981). Communicative Language Teaching: An Introduction. Cambridge: CUP.

Long, M. H. (1975). Group work and communicative competence in the ESOL classroom. In M. K. Burt & H. C. Dulay (Eds.), On TESOL ’75: New Directions in Second Language Learning, Teaching and Bilingual Education. Selected Papers from the Annual TESOL Convention (9th, Los Angeles, CA, March 4-9, 1975) (pp. 211-223). Washington D.C.: TESOL.

Long, M. H. (1976). Encouraging Language Acquisition in a Formal Instructional Setting. ELT Documents 76(3). London: British Council.

Long, M. (2015). Second Language Acquisition and Task-based Language Teaching. Chichester: Wiley.

Long, M. (1985). A role for instruction in second language acquisition: Task-based language teaching In K. Hyltenstam & M. Pienemann (Eds.), Modeling and assessing second language development (pp. 77–99). Clevedon, Avon: Multilingual Matters.

Maley, A. (1981). Games and problem solving In K. Johnson & K. Morrow (Eds.), Communication in the Classroom (pp.137-148). Harlow: Longman.

Morrow, K. & Johnson, K. (1979). Communicate 1 Teacher’s Book. Cambridge: CUP.

Morrow, K. (1981). Principles of communicative methodology. In K. Johnson & K. Morrow (Eds.), Communication in the Classroom (pp.59-66). Harlow: Longman.

Nakahama, Y., Tyler, A., & van Lier, L. (2001). Negotiation of meaning in conversational and information gap activities: A comparative discourse analysis. TESOL Quarterly 35(3), 377-405.

Pica, T., Kanagy, R., & Falodun, J. (1993). Choosing and using communication tasks for second language instruction. In G. Crookes and S. Gass (Eds), Tasks and Language Learning: Integrating Theory and Practice (pp. 9-34). Clevedon, Avon: Multilingual Matters.

Prabhu, N. S. (1987) Second language pedagogy. Oxford: OUP.

Redston, C. & Cunningham G. (2013). Face2Face Intermediate, Student’s Book (2nd Ed.). Cambridge: CUP.

Rixon, S. (1979). The ‘Information Gap’ and the ‘Opinion Gap’—Ensuring that Communication Games are Communicative. ELT Journal, 33(2), 104-106.

Soars, J. & Soars, L. (1991). Headway Pre-Intermediate, Student’s Book (1st Ed.). Oxford: OUP.

Swain, M., & Lapkin, S. (2001). Focus on form through collaborative dialogue: exploring task effects. In M. Bygate, P. Skehan and M. Swain (Eds.), Researching Pedagogic Tasks: Second Language Learning, Teaching and Testing (pp. 99–118). New York: Longman.

Swan, M., & Walter, C. (1985). The Cambridge English Course Student’s Book. Cambridge: CUP.

University of Birmingham. (1972). Concept 7-9. Leeds: E. J. Arnonld, for the Schools Council.

Ur, P. (1981). Discussions that work. Cambridge: CUP.

Walz, J. (1996). The classroom dynamics of information gap activities. Foreign Language Annals, 29(3), 481-494.

Watcyn-Jones, P. (1978) Act English. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Wright, A. (1976). Visual Materials for the Language Teacher. London: Longman.

Thanks for the very interesting post!!

Actually, I have a question regarding the interdisciplinary origin of the term “information gap”. As you probably know, “Information/knowledge gap” is also a theory in communication/information studies that was popolar in the 60’s and 70’s. (see for example: Tichenor, Donohue & Olien, 1970). The basic assumption of this theory is that information is not equally distributed in society. This generates an ever increasing information gap between the “information rich” and “information poor ” https://helpfulprofessor.com/knowledge-gap-theory/. The proponents of this theory discussed on ways to “fill this gap” in order to create a better society.

My question is: do you think that this definition of “information gap” had any impact on Aronson (or other scholars of that time)? Thanks in advance for your time and thanks again for your very stimulating research!

LikeLike

Hi Mattia, Thanks for reading. Aronson didn’t actually use the term ‘information gap’. It becomes popular in the more specific field of language teaching as the communicative movement kicks in. While I’m not certain, I strongly suspect it may have been borrowed initially from the field you mention, although it was floating around in a range of areas of research in the 1960s – see this targeted Google Scholar search: https://scholar.google.co.uk/scholar?as_q=&as_epq=information+gap&as_oq=&as_eq=&as_occt=any&as_sauthors=&as_publication=&as_ylo=1950&as_yhi=1970&hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5

LikeLike

Dear Jason, thanks for the clarification and the link that shed a very interesting light on the intellectual cross-pollination during those days. Good luck with your research: I think that a material history of the field of SLA could be very beneficial both for scholars and for practitioners (like me).

LikeLike