Anyone who speaks two or more languages will be aware that there are linguistic ‘gaps’ in all languages. Given that English is now established as the predominant lingua franca of the world, the existence of such gaps can be at best inconvenient, and at worst, it may influence what we say or think (depending on how much you agree with the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis).

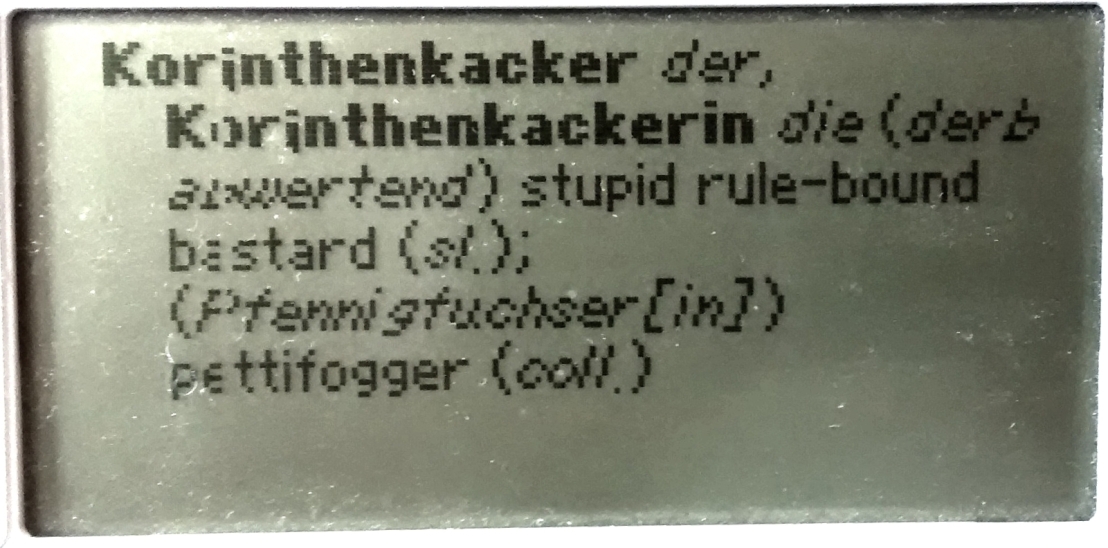

However, this blog is not about the many interesting and insightful words, often from more synthetic languages that we don’t have, or simply borrow to express the ideas behind them. Well-known examples from German include ‘Schadenfreude’ and ‘Gestalt’, although my personal favourite came up in a lesson last year: ‘Korinthenkacker’. A translation device rendered it as: ‘stupid rule-bound bastard’. Luckily, the student was referring to a childhood teacher, not me!

No, this blog isn’t about ‘Korinthenkackers’… luckily. It’s about how English sometimes doesn’t have an appropriate way to convey something that commonly needs to be expressed. Holes in the language, if you like.

Here are some of the most obvious examples. If you can think of any more, please leave a comment!

| English lacks… | Other languages? |

| …a phrase for ‘bon appétit’ | Most other languages have a phrase. We usually borrow the French expression. ‘Enjoy your meal’ (usually American English) is more likely to be said by a waiter than a co-diner. |

| …a ‘you’ singular/ plural distinction | Most languages have such a distinction, and English lost it quite recently – there are still a few areas of Yorkshire where ‘thou’ is still used. Interestingly, plural versions of ‘you’ are evolving back into English, reinforcing the importance of this difference, with ‘yous’ used in Northern Ireland and ‘y’all’ , common in some southern American states. |

| …a word for ‘halas’ (Arabic), ‘basta’ (Italian), ‘hvateet’ (Russian), ‘beka’ (Tigrinya), etc. | Almost every other language I’ve learnt seems to have one word to indicate sufficiency, making it convenient when we need to be quick. In different situations we might render it as: ‘stop there’, ‘that’s enough’, ‘that’s it’, ‘I’ve had enough’, etc. It would be useful, faster and much simpler to have one, rather than having to choose from these alternatives. |

| …a non-gender third person singular pronoun | For example: “if anyone has any ideas, she/he should…’ While not so many languages have such a pronoun (Sweden successfully invented one), given the increasing importance of sexual equality in English, there is a clear demand for such a word. Many argue that we should simply use ‘they’ in such situations, but it doesn’t always fit and can be surprisingly confusing to language learners. |

| English lacks… | Other languages? |

| … a colour | ‘Sky blue’ or ‘navy blue’? This may sound like a strange distinction to some monolingual speakers of English, who may perceive that these are simply different types of blue. But it’s interesting to note that many languages have this distinction. Russian has ‘goluboi’ and ‘siniy’, and Italian has ‘azzurro’ and ‘blu’. Whenever in either of these languages I use the ‘wrong’ blue, I get corrected. It’s similar to the red/pink distinction in English. One is a lighter version of the other, but they remain separate concepts, separate things in our mind, each with very specific associations. Pink is the colour for girls in English (not ‘red’, or ‘light red’), ‘goluboi’ also means ‘gay’ in Russian, and ‘il principe azzurro’ is ‘Prince Charming’ in Italian. |

| …plurals for some of the most common words | In many lingua franca and world Englishes, ‘information’ can be pluralised, saving time and energy. However, native-speaker varieties of English stubbornly resist these logical innovations. ‘Three informations’ is much shorter than ‘three pieces of information’. Other examples include ‘advice’, ‘furniture’, ‘research’, ‘evidence’, ‘equipment’. We don’t even pluralise ‘money’, kind of ironic for a culture that invented capitalism! |

| …a ‘proper’ future tense | Any English language teacher will know that English has a complex variety of ‘future forms’ (e.g. ‘will’, ‘be going to’ + infinitive, etc.) but no way to distinguish the future morphologically. We can add ‘-ed’ to ‘work’ to form the past, but unlike French (‘travaillerai’) or Spanish (‘trabajaré’), we have no morpheme to make it future. |

| …a word to describe ‘the day after tomorrow’, or ‘the day before yesterday’ | A number of the websites describing colourful words that English doesn’t have point out that Georgian has a word for the day after tomorrow (it’s ‘zeg’ apparently)… and so does Russian (‘poslezavtra’). It also has a word for the day before yesterday (‘pozavchera’**). Why use four, when you can use one? |

| English lacks… | Other languages? |

| …consistency when describing the years after 2000 | Does anyone else find the word ‘noughties’ not very helpful to describe the decade between 2000 and 2010? The conversation often goes like this:

A: ‘I think it was some time in the noughties?’ B: ‘In the nineties? No it was later than that!’ A: ‘No. I said in the “noughties”?’ B: ‘The what-ies’? etc. Even more important: do we say ‘twenty-sixteen’ or ‘two thousand and sixteen’ for ‘2016’? And for those who prefer the latter, why is it that we should suddenly change now after so many centuries? It’s two syllables and 10 characters longer! |

| …words for ‘smell’ | Try translating the following joke into another language:

A: My dog has no nose. B: How does it smell? A: Awful. It probably doesn’t work. Why? Because in most other languages, these two meanings of the word ‘smell’ are usually expressed through different verbs. Try translating these into another language and see how many options you get: 1. The flowers smell beautiful. 2. This room smells! 3. I can smell fire. 4. Smell this. |

| English lacks… | Other languages? |

| …a simple way to say: ‘We are three.’ | In standard varieties of English, you can’t say this. You have to say: ‘There are three of us.’ But why not? It’s clear. It is common in lingua franca varieties of English, and it’s generally a direct translation of what is said in many other languages. |

| …a universal tag question (US) / question tag (Br.)

|

Most languages have these. In German it’s ‘oder?’, in Chinese ‘ma?’ and in Bahasa Indonesia ‘kan?’ This creates significant difficulties for English language learners who have to work out what the auxiliary verb for the statement is and invert it with the subject: ‘It’s cold today, isn’t it?’, ‘You can’t smoke here, can you?’, ‘They moved here last year, didn’t they?’, etc. Due to these complexities, this common feature of spoken language is often acquired very late within the natural acquisition of second language learners. |

| Additions from | readers |

| …a verb to describe how submarines move | From Ken Lackman:“What is the verb for what a submarine does when moving forward? We need it for any vessel that moves through water that doesn’t sail. I noticed this when one of my students (who was Czech) talked about a submarine swimming. I corrected him but when he asked for the correct verb, I had nothing. He also asked why we used “fly” for anything that flew other than birds and why we don’t use “swim” for things that swim besides fish (and other water creatures). I had, of course, no answer. |

| …a difference between romantic love and friendly love. | From Pablo: “In Spanish we say “te amo” and “te quiero”, respectively.” Thanks Pablo – The same is true in Italian – ‘Ti voglio bene’ and ‘Ti amo’. You cannot say the latter to your parents! And in Ukrainian they have a separate verb for loving people – ‘Kohayu tebe’ (I love you), and things – ‘Lyublyu shokolad’ (I love chocolate). |

| …a word for ‘Which-th’ | From Blah: “I sometimes find the absence of “which-th” in English inconvenient: “Whichth child of your parent are you” – as in first, or second, or third,…? This word is there is some, if not all, south Indian languages” |

| …an equivalent for RSVP | From Macadamia Wightman: “RSVP – no English word for that!”

RSVP stands for “Respondez s’il vous plait” – in case you weren’t sure. It’s used on invitations in the UK, US, etc. despite being French. |

| … enough words for family members and relatives | From Patrick Snook: “We don’t have a word in English for “adult child/children”. “Offspring” or “progeny” don’t imply any particular age. I can refer to my child, but what do I say when he’s 18 or older, and no longer a child? ”

From Daniel Benson: “big brother/sister versus little brother/sister (Bulgarian “kaka i batko” vrs. “sestra i brat”)” and “In Bulgarian, there are terms of address from child-to-parent and from parent-to-child based on the old vocative and genative declensions. For example, the uninflected word for “mother” is _mama_, but children talking to their mothers say _mamo_ and mothers talking to their children call them _mame_.” From Joseph Edwards: “English has no way to recreate the effect of Vietnamese’s kinship pronouns (where instead of using ‘you’ and ‘I’ you use your relative ages and the closeness of your relationship to name yourselves ‘big sister/brother’, ‘younger sibling’, ‘aunt’ etc.), which have a wonderful effect of being able to make your contribution simultaneously more polite and more affectionate.” From Greg Bard: “I would also propose the word “avunculi” as the collective word for aunts and uncles.” From Madhav: “Tamil and Telegu also have separate words for maternal and paternal uncles (and aunts).” From Peter Borrows: “My son is married to your daughter. How are we related, or rather what English word describes our relationship? That’s a hole in English, whether or not there is a word in French, Tamil, etc.” From Shankar Raman: “English language does not have separate words for maternal and paternal aunts, uncles and grandparents. These words are common in Sanskrit, besides other Indian languages.” |

| …diminutives | Diminutives are especially common in Slavic languages, and especially with names (e.g. If your name is Olga, others could call you Olya, Olka, Olenka and Ola). Adding ‘-ok’ to ‘Chai’ makes ‘Chaiyok’ (a little tea). In essence, the word ‘vodka’ derives from the word ‘water’ (voda) with the diminutive suffix ‘-ka’!

From Daniel Benson: “diminutive verbs (Bulgarian “govorkam” I cutely speak)” From kmmoerman: “3. Morphing words to refer to smaller versions. E.g. the Dutch “-je” in “boekje” refers to “a small book” and “stukje” means “a small piece/a little bit” (me and my wife use the term bittle to refer to little bit).” |

| …two types of’shame’ | From Alexandros Olivis: “The versatile meaning of the word ‘shame’ like “shame on you” and “shame you couldn’t be here”. It should be two different words.”

This can lead to misunderstandings in English. I know a native speaker who once wrote ‘shame you couldn’t come to the meeting’, which was interpreted as ‘shame on you for not coming…’, leading to the latter party taking offence. |

It might not qualify because I’m comparing only two languages here, but when switching from Vietnamese into English, or translating in the same direction, I find English has no way to recreate the effect of Vietnamese’s kinship pronouns (where instead of using ‘you’ and ‘I’ you use your relative ages and the closeness of your relationship to name yourselves ‘big sister/brother’, ‘younger sibling’, ‘aunt’ etc.), which have a wonderful effect of being able to make your contribution simultaneously more polite and more affectionate. I think English ways of being polite often distance you from the interlocutor, rather than emphasising your kinship like this. It is a really miraculous feature of Vietnamese I think!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Interesting. In Bangla there are similar forms of address based on kinship (but not pronouns), which I found really useful on a recent consultancy project there.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The day before yesterday is “ereyesterday.” The day after tomorrow is “overmorrow.” Both of these are known and accepted. I propose the following order: forepreanteereyesterday, preanteereyesterday, anteereyesterday, ereyesterday, yesterday, today, tomorrow, overmorrow, postovermorrow, eftpostovermorrow, umbeftpostovermorrow. This is consistent with ultimate, penultimate, antepenultimate, preantepenultimate, forepreantepenultimate.

Any New Yorker will tell you that “youse” is the plural form of “you.”

The gender neutral third person singular is “he or she,” “she or he,” “him or her,” or “her or him” as appropriate. Logical connectives exist for a reason. Use them.

The “future tense” does not exist because the future doesn’t exist. The “future tense” is a modality of the present tense.

I would also propose the word “avunculi” as the collective word for aunts and uncles.

LikeLike

Thanks Greg. RE: Future tenses – they exist in other languages, so perhaps this is a specifically English-determined idea that future is expressed as a modality (or continuation – I’m having lunch with him) of the present.

LikeLike

about future tenses: romanic languages (french, spanish and so on) often have one while germanic languages (such as english and german) don’t. interestingly, there is also a different style of acting towards future events, handling philososphy and history to be seen in these cultures. I once read an interesting essay on that but forgot the title…

LikeLike

Excellent article. It’s “pozavchera” not “polsevchera”, though.

As for examples, I do stumble upon these when I write all the time, thinking of the concept in one language then finding it hard to to translate it in the language that I am actually writing in, but I can’t think of any right now. I recently thought щелбан was a concept that didn’t exist in English, but turns out it kinda does, it’s just archaic. (It means a ‘fillip’ to someone’s forehead. A word in the same useful category as a noogie (no analogue in Russian) or kancho.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

** Thanks – corrected above! My Russian is getting a bit rusty!

LikeLike

My favorite in Spanish: the equivalent of “being in someone’s memory”, but for “that body of things someone has forgotten”: “en el olvido”.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting – can you provide an example, and I’ll add it above and credit you?

LikeLike

A differentiation between romantic love and friendly love. In Spanish we say “te amo” and “te quiero”, respectively.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Of course! The same is true in Italian – ‘Ti voglio bene’ and ‘Ti amo’. You cannot say the latter to your parents! And in Ukrainian they have a separate verb for loving people – ‘Kohayu tebe’ (I love you), and things – ‘Lyublyu shokolad’ (I love chocolate). I’ll add your suggestion and credit you. Many thanks!

LikeLike

I sometimes find the absence of “which-th” in English inconvenient: “Whichth child of your parent are you” – as in first, or second, or third,…? This word is there is some, if not all, south Indian languages.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Interesting! Added above! Thank you.

LikeLike

Nice list. Two comments: The Russian for “the day before yesterday” is “pozavchera”. Also, “*All* other languages have a phrase for ‘bon appetit'” is a very strong claim! Is that really true?

I can’t think of other examples at the moment, but I’ve always found it odd that English-speakers are forced to turn to German for a secular response to someone sneezing. It seems like the appropriate phrase in most languages refers to health, whereas only a distinct minority appeal to a deity. We got stuck with the latter, I guess.

LikeLiked by 1 person

** Thanks – corrected above! My Russian is getting a bit rusty! And ‘all’ has been modified. Cheers!

LikeLike

Love this blog! Here are my suggestions:

diminutive verbs (Bulgarian “govorkam” I cutely speak)

subjects for past participle adjectives (Bulgarian “mit ot men kola” the washed-by-me car)

augmentative nouns (Bulgarian “valchishte” dire wolf)

compound verbs (Japanese “ittekimasu” I go and come “yondetabemasu” I drink and eat)

evidentials (Bulgarian “Bih bil napil” I am told I was drunk, but I don’t believe it.)

a reflexive particle (Bulgarian “se” (intransitive) and “si” (transitive), dial. English “me” “Shte si kupi knigi!” I’m gonna by me some books!)

a resigned acceptance of circumstance like (Japanese “yappari”)

to work hard, to try your best (Japanese “ganbaru”)

a way to describe how far your nose sticks out from your face (Japanese “hana ga takai” your nose is “tall”)

dreams you hope vs see while sleeping (Bulgarian “mechta” vrs “san”)

big brother/sister versus little brother/sister (Bulgarian “kaka i batko” vrs. “sestra i brat”)

LikeLiked by 1 person

I thought of two more 🙂

In Bulgarian, there are terms of address from child-to-parent and from parent-to-child based on the old vocative and genative declensions. For example, the uninflected word for “mother” is _mama_, but children talking to their mothers say _mamo_ and mothers talking to their children call them _mame_. The same works for other kinship terms (a bit like Vietnamese kinship pronouns), so when someone calls you _babe_, you know she thinks you’re like a grandchild to her. It’s also convenient to say be able to say_something something, babo_, and any grandmother in the room knows that you are addressing her.

LikeLike

We typically use ‘lying’ to mean something like: asserting something you know to be false.

But even if you think your statement *probably is* true, you might still be guilty of overstating the certainty you could reasonably assign to that belief.

If you tell me my parachute is properly packed, I don’t just expect you to think that’s probably true (ie not be lying) but also to have good reason to be as certain about that as your assertion suggests.

I’d like a word for that to be in common usage. It’s absence leaves us judging perpetrators as either lying or (all too often) blameless.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Evidentials would solve that problem.

In Bulgarian you’d say:

_Parashutat e opakovan_ “The parachute is packed” (I either did it or saw it done) Indicitive

_Parashutat e bil opakovan “The parachute is apparently packed” (it looks like someone did it) Inferential*

_Parashutat bil opakovan_ “Someone told me the parachute is packed” (I got news of it) Renarrative

_Parashutat bih bil opakovan_ “Yeah right, the parachute is ‘packed'” (I don’t believe it) Dubitative

*often used to translate the English present perfect

(Bulgarian speakers please correct me if I made any mistakes)

LikeLike

Last one 🙂

Related to the “which-th” or question word as in South Indian languages, it would be nice if English had a single word for “how many.” Not only would you be able to ask “how many/which-th child are you?”, but answer with “I don’t remember. I’m the how-many-ever-th child.” You could also tell someone to “take how-many-ever you need” in the same way as you can say “take whatever you need.” You could also say “How-many-ever we are, we can win.”

Oh, and causatives! (Japanese _hanasareru_, “I make someone speak”)

And inclusive versus exclusive plural first person constructions! (Tok Pisin _Yumi stap pikinini_ “We (and you also) are kids” versus _Mipela stap pikinini_ “We (but not you) are kids.”)

I’ll stop now.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow! That’s quite a list Daniel. Many thanks!

Jason

LikeLiked by 1 person

Two south Indian languages I know (Tamil and Telugu) have two variants of “we” or “us”. One variant includes the second person you are talking to, while the other doesn’t. That distinction is lacking in English.

These two languages also have separate words for maternal and paternal uncles (and aunts).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes – the ‘we’ including listener vs. ‘we’ not including listener is found in several language groups, I believe. Thanks for this!

LikeLike

It would be helpful if I could describe x and y as something less cumbersome than my child’s spouse’s parents.

LikeLike

We lack a word for “adult child (or children)”. I can talk about my offspring, but that could be any age, and one or more. My child (or children) works–but surely not if my “child” is 18, 21, 56. . . .

LikeLike

Yes, two distinct versions of ‘we’ would get my vote too! And isn’t a Korinthenkackers similar to a jobsworth?

LikeLike

1. Dutch/german: gemütlich/gezellig.

2. German: überhaupt

3. Morphing words to refer to smaller versions. E.g. the Dutch “-je” in “boekje” refers to “a small book” and “stukje” means “a small piece/a little bit” (me and my wife use the term bittle to refer to little bit).

LikeLike

Thanks for this Kevin. These morphed words are often called ‘diminutives’. They are common in Slavic languages too. As my name is Jason, my ex used to call me ‘Jessica’ ‘-ka’ is a Russian way of making something smaller / more precious.

LikeLike

My son is married to your daughter. How are we related, or rather what English word describes our relationship? That’s a hole in English, whether or not there is a word in French, Tamil, etc.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Absolutely fascinating post. ‘yous’ is common in the Newcastle area of the UK as well. I definitely feel the lack of diminutives in English.

Ken mentioned about submarines swimming in Czech. Both submarines and boats swim in Slavic languages as far as I know – they certainly do in Polish, which I’m learning at the moment, and I seem to remember that they do in Russian too.

Thanks Jason.

Sandy

LikeLiked by 1 person

We don’t have a word for “adult child(ren)”. “Offspring” or “progeny” can refer to one ore more of no particular age. But I don’t know of a word for referring to my child (or someone’s children), which means adult-child (or adult-children).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting, though none of the other Germanic languages have a ‘proper’ future tense either, they use a modal auxiliary verb – German uses söllen, Dutch uses zullen, both of which come from the same root as ‘shall’, while Danish uses ‘vil’ or ‘skal’, cognate with ‘will’ and ‘shall’.

As regards a plural form of ‘you’, ‘jullie’ in Dutch comes from ‘je lui’, meaning ‘you lot’, ‘je’ being the singular form of ‘you’, which supplanted ‘du’ in Dutch just as ‘you’ supplanted ‘thou’ in English. In most other Germanic languages (except Afrikaans, which is an offshoot of Dutch) ‘du’ is used, or ‘do’, used in Frisian.

‘Enjoy!’ is used in the UK, which John Humphrys of the BBC gripes about because it’s not an intransitive verb, although it’s a translation of the Yiddish ‘hob anoe!’ meaning ‘have enjoyment!’. Many American English expressions are calqued on German, Yiddish or Dutch.

LikeLiked by 1 person

English language does not have separate words for maternal and paternal aunts, uncles and grandparents.

LikeLike

Good point. I believe such words are quite common in ‘Sanskrit’ languages. Do you happen to know?

LikeLike

Yes, these words are common in Sanskrit, besides other Indian languages.

LikeLike

English lacks single-word verbs for “closing one’s eyes” and “opening one’s mouth”.

In Swedish, “Gapa och blunda!” means “Open your mouth and close you eyes!”.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Ulrika. Are there any other languages where this is true?

LikeLike

Not that I know of. Not even our closest relatives, the Danes and Norwegians, have these practical words.

LikeLike

It looks like Swedish “gapa” is cognate to English “gape,” which does in fact mean “open your mouth.” “Blunda” looks like it’s cognate to “blind.” But it would be weird in English to say “Gape and blind!” Maybe we can start a fashion. 🙂

LikeLike

“Gape” comes from Old Norse “gapa”, to be sure. “Blind” is of common Germanic etymology.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on ESLearning and commented:

Great comments on English Language linguistic ‘gaps’

LikeLike

Many thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi, just wanted to thank you for this article. We’ll try it with our students.

LikeLiked by 1 person